UTOPIE MÉCANIQUE:

Laboratoire de machines imaginaires…

Mes recherches portent sur les mécanismes du mouvement et les interactions possibles entre l’utilisateur et l’appareil. Je mets en place des dispositifs qui viennent se greffer sur le corps, tels une prothèse qui viendrait prolonger un membre. Suivant mes mouvements, la machine s’anime donnant naissance à un être hybride.

Mes recherches portent sur les mécanismes du mouvement et les interactions possibles entre l’utilisateur et l’appareil. Je mets en place des dispositifs qui viennent se greffer sur le corps, tels une prothèse qui viendrait prolonger un membre. Suivant mes mouvements, la machine s’anime donnant naissance à un être hybride.

L’ensemble de mon travail se présente sous forme de laboratoire où les prototypes ratés côtoient les projets en cours, où les formes ne sont pas figées, mais sont destinées à évoluer dans le temps. Je les améliore sans cesse grâce à de nouvelles expériences.

C’est une réflexion sur le corps humain et comment l’améliorer par soi même. Une obsession de devenir plus qu’un Homme, qui fini par échouer.

En effet, malgré la fonctionnalité et l’efficacité des mécanismes mis en place, mes pièces demeurent fragiles et contraignantes pour l’utilisateur. Au lieu d’améliorer ses capacités physiques, elles les restreignent. Cet échec est l’objet même de ma démarche artistique.

Mon travail témoigne des limites de l’humanité, tout en célébrant le désir de vouloir la transcender. J’aborde donc des notions de transhumanisme et le concept de Post humain à travers des représentations plastiques qui mettent en avant le corps et sa transformation via des améliorations physiques.

Le dépassement auquel je fais référence étant individuel, j’apporte beaucoup d’importance au fait de réaliser ces orthèses par moi même : avec les compétences techniques que j’acquière et perfectionne au fur et à mesure. Le choix des matériaux utilisés – souvent en décalage avec le mécanisme développé – a pour but de renforcer le potentiel fantasmagorique de l’ensemble, mais aussi de le sublimer d’un point de vue sculptural. L’utilisation du bois par exemple force le rouage d’un système mécanique à changer de forme, de même que dépourvu de sa fonction une machine révèle toute l’esthétique de son design.

Finalement, ces sculptures dont les fonctions réelles sont limitées, font appel à l’imaginaire afin de s’accomplir en tant que machines.

« Les machines de Jonathan Sitthiphonh pourraient rappeler l’univers S.F. – les robots exosquelettes dans les films de James Cameron, notamment. Par leur archaïsme, elles pourraient aussi rappeler l’ingénierie léonardienne. Coincées entre le mythe d’Icare et le post-humain, elles matérialisent un rêve de dépassement des limites humaines. Mais sans l’exaucer.

« Les machines de Jonathan Sitthiphonh pourraient rappeler l’univers S.F. – les robots exosquelettes dans les films de James Cameron, notamment. Par leur archaïsme, elles pourraient aussi rappeler l’ingénierie léonardienne. Coincées entre le mythe d’Icare et le post-humain, elles matérialisent un rêve de dépassement des limites humaines. Mais sans l’exaucer.

L’entreprise de l’artiste est ambitieuse, motivée. Il réalise minutieusement, à la main et avec des matériaux de récupération, ces prothèses en perfectionnement.

Malgré les prouesses, elles restent fragiles et inefficaces, vouées à l’inertie. Elles n’atteignent pas le but pour lequel elles sont construites.

Que l’artiste se soit détourné d’un parcours scientifique pour intégrer le monde de l’art, révèle sa lucidité sur ses échecs. Ne pourraient-ils pas, d’ailleurs, être une fin en soi ? Les belles machines, techniquement ineptes, conservent un pouvoir d’évocation et un potentiel imaginaire. Si elles tendent vers un dépassement des moyens humains, elles en célèbrent justement les limites. Elles sont le fruit d’une ambition revue à la baisse. L’artiste assume pleinement sa position de Da Vinci du dimanche, libéré de la performance, du progrès, du génie. Il persévère dans la précarité et l’imperfection avec enthousiasme, mû par un désir de bien faire et faire rêver. En cela, il réussit ».

Sébastien Martins, assistant d’exposition au Palais de Tokyo. (2012)

Sculptures Provoke Thought Through Motionless Devices

Sculptures Provoke Thought Through Motionless Devices

ITO Satoko

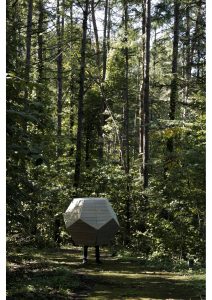

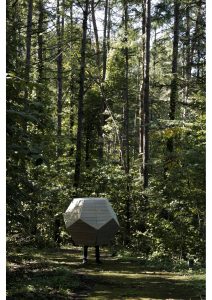

« Jonathan SITTHIPHONH produced two sculptures for the 2016 Autumn Artist in Residence (AIR) Program. As their title Cocoon suggests, they are pupa-like structures with hollow interiors. One of the cocoons is a type of micro-architecture just large enough for one person to crawl in. The other cocoon has a wearable wooden frame made to mimic an insect’s shell and can be opened and closed like an accordion. Gaps at regular intervals within their structures allow moderate light to reach the interior. Both are small spaces that force you to hunch down and look inside yourself, which he uses as devices to promote future change through introspection.

The photographs displayed together with the works show the artist within, or wearing, the sculptures. The thick, raised frames that surround the photographs, made of the same wood as the sculptures, show that they are a piece of the sculptures themselves. The array of photographs connects the function of the devices with the imagination, and the empty shells on display give off a presence, without showing a human shape. Is this just the trace of some former transformation, or is the transformation still to come?

The photographs displayed together with the works show the artist within, or wearing, the sculptures. The thick, raised frames that surround the photographs, made of the same wood as the sculptures, show that they are a piece of the sculptures themselves. The array of photographs connects the function of the devices with the imagination, and the empty shells on display give off a presence, without showing a human shape. Is this just the trace of some former transformation, or is the transformation still to come?

In his previous work, Sitthiphonh has produced wearable, robot-like wooden sculptures and explored the mechanism of movement and the interaction between person and machine. In contrast to his previous work and in consideration of the exhibition theme, Time For A Change, he has focused on the moments when people transformation. It is a prologue into the process that produced his earlier works.

Sitthiphonh himself calls the studio where he usually works his “laboratory.” There his failed projects stand alongside current works in progress as he endlessly improves them unless they are out on display.1 His attitude is like that of both artist and researcher, perhaps influenced by his penchant for making things since childhood and in part by his academic background in science. Sitthiphonh’s art is shaped by constant experimentation with forms proven by science and aide by a combination of imagination and the skill to create with his own two hands.

During his stay, he would begin working on an idea as soon as it came to him, acting immediately without planning out the details of his design. Though not quite the chemical reactions of a true laboratory, with cardboard and wood chips from the Creative Hall, his ideas instantly turned into models. While there is no shortage of ideas with him, it can be difficult to give an immediate shape to something that exists only as some unseen imagination. Designs and calculations can be found on the internet of course, but even if the plans are accurate, working with actual wood is different, so one slight miscalculation can make it impossible to achieve the desired form, and it becomes necessary to make one wooden model after another.2 And when working at other resident productions, he must explore production methods according to the properties of the woods used there. This time, to make a shape that combines thin, curving pieces of wood, he repeated trial productions many times looking for a suitable material that would bend but not break.

During his stay, he would begin working on an idea as soon as it came to him, acting immediately without planning out the details of his design. Though not quite the chemical reactions of a true laboratory, with cardboard and wood chips from the Creative Hall, his ideas instantly turned into models. While there is no shortage of ideas with him, it can be difficult to give an immediate shape to something that exists only as some unseen imagination. Designs and calculations can be found on the internet of course, but even if the plans are accurate, working with actual wood is different, so one slight miscalculation can make it impossible to achieve the desired form, and it becomes necessary to make one wooden model after another.2 And when working at other resident productions, he must explore production methods according to the properties of the woods used there. This time, to make a shape that combines thin, curving pieces of wood, he repeated trial productions many times looking for a suitable material that would bend but not break.

Despite its physical hardness, wood retains the same conceptual softness of any other living creature. Sitthiphonh uses it in his art to great effect beyond merely expressing an opposing relationship when he gives an artificial shape to this natural material.

His past works include a wearable sculpture with a wing mechanism. The wooden wings are reminiscent of Icarus, who was outfitted with wings crafted out of wax and feathers. But humans cannot fly when outfitted with Sitthiphonh’s sculptures. Despite the capabilities of the mechanisms themselves, the devices are devoid of function when rendered as wooden sculptures. Rather than enhance physical function, the devices actually restrict and hinder their user.

This failure to achieve a designed function connotes the contradiction that occurs when humans try to become something more than human—the absurdity of surpassing humanity by human means. In this respect, Sitthiphonh’s failures of function are not in fact failures but questions. He intentionally does not allow them to function, posing to questions the viewer through the presentation of contradiction—devices stripped of their function. A loss of function invites a look into the aesthetic of the mechanism’s design. It urges our imaginations to fill in the rest of the story. And so these sculptures start to function as imaginary mechanisms.

On the other hand, the power and comicality with which these mechanisms move succeed in humorously encapsulating a paradoxical view of humanity and an inescapable sense of emptiness that accompanies a device that must be left incomplete. But the human element hidden behind the mechanisms gives them a certain charm. From the perspective of sculpture, the larger the gap between the logic and delicate craftsmanship behind a work and the frailty of its function, the stronger the impression.

On the other hand, the power and comicality with which these mechanisms move succeed in humorously encapsulating a paradoxical view of humanity and an inescapable sense of emptiness that accompanies a device that must be left incomplete. But the human element hidden behind the mechanisms gives them a certain charm. From the perspective of sculpture, the larger the gap between the logic and delicate craftsmanship behind a work and the frailty of its function, the stronger the impression.

Sitthiphonh has continued to use irony to question the evolution of technology and what it means to be human. In trying to exceed the abilities given to us, we are restricted. In other words, we can only be human—nothing more. However riddled with contradiction, humans continue their pursuit of evolution. This view of humanity mirrors Sitthiphonh’s unique artistic stance to endlessly improve his works. While this may be considered normal for artists, he continues to improve his works in his laboratory according to new skills learned and experiences gained without a definitive final shape or form. Additionally, he also reveals the processes within his work as he creates. His attitude shows a way of life as well as a joy for the act of production itself. It is almost as if he is offering one possible answer to the very question he poses.

In his cocoons, people enter a process of transformation and evolution. They envelope the entire body, which is distinct from his previous works, many of which were designed to be worn on the body as robot-like extensions of the limbs. From outside, we lose sight of the human shape, and that allows us to imagine a transformation into something entirely different taking place inside the cocoon. We are once again reminded that the human imagination, which is important for these devices to work, allows us to march forward into the unseen, even if it cannot completely stamp out contradiction and impossibility.

It is human nature to use this power to make imagination a reality.

In his cocoons, people enter a process of transformation and evolution. They envelope the entire body, which is distinct from his previous works, many of which were designed to be worn on the body as robot-like extensions of the limbs. From outside, we lose sight of the human shape, and that allows us to imagine a transformation into something entirely different taking place inside the cocoon. We are once again reminded that the human imagination, which is important for these devices to work, allows us to march forward into the unseen, even if it cannot completely stamp out contradiction and impossibility.

It is human nature to use this power to make imagination a reality.

The questions posed by the artist contain a message that encourage introspection and transformation. At the same time, the egg-like shape of his cocoons is symbolic of hatching new ideas through imagination. There is no doubt that his next devices will emerge reborn from their cocoons and begin to move with the imagination of those who see them.

1 Lecture during exhibition-related event on December 3, 2016

2 Ibid.

問いかける彫刻、動かない装置

伊藤聡子

ジョナサン・シティフォンは、今回のAIRで2つの彫刻を制作した。タイトルにある「コクーン」が示す通り、彫刻はサナギのように中が空洞となっており、それぞれ人が一人入れるほどの小さな建築と、昆虫の甲殻を模して組まれた木のパーツが蛇腹式に開閉、さらに装着可能な形態になっている。これらの彫刻は構造上にできる規則的な隙間によって内部に程よく光を与える。これらの小さな空間は身をかがめさせ、自身の内面へと集中させる。内省を促し、人を変化させるための装置だ。

作品とともに展示されている写真は、作家本人が彫刻の中に入る/装着している様子を撮影したものだ。そのフレームに彫刻と同じ素材が用いられ、さらに立体的な厚みを持たせることで、彫刻の一部であることを示す。連続した写真のイメージによって装置が持つ機能を人の想像の中に繋ぎあわせ、そこに佇み/吊られた抜け殻は、これから変化が起こる、または変化を終えた跡なのか、人の形を見せずに気配だけを感じさせる。

作品とともに展示されている写真は、作家本人が彫刻の中に入る/装着している様子を撮影したものだ。そのフレームに彫刻と同じ素材が用いられ、さらに立体的な厚みを持たせることで、彫刻の一部であることを示す。連続した写真のイメージによって装置が持つ機能を人の想像の中に繋ぎあわせ、そこに佇み/吊られた抜け殻は、これから変化が起こる、または変化を終えた跡なのか、人の形を見せずに気配だけを感じさせる。

シティフォンは、これまで人の身体に融合し手足の機能を高めるロボットのような木の彫刻作品を制作し、動きのメカニズムと、人と機械の間に起こる相互作用を探求してきた(fig.1)。それらに対し今回は、展覧会のテーマである「Time For A Change」に沿い、人が「変化する時間」に焦点を当て、これまでの作品が生まれる過程の前編として制作された。

普段制作しているスタジオを作家は自ら「実験室」(⇐ルビをラボラトリーとして下さい)と呼んでいる。「実験室」の中では、失敗作も含めたこれまでの作品を共に並べ、展示をするために外に出している時以外は常にそれらに改良の手を加え続けているのだという(1)。アーティストでありながら、研究者のような姿勢は、子供の頃から自然に物作りを続け、さらに科学を学んだ経験から育んだのだろうか。科学的な視点で実証できる形を求め常に実験を重ねることと、そこに自分の手で物を作り出す技術と想像力を合わせることで、シティフォンのアートが形作られている。

滞在中、アイディアが決まると設計図も描かずに早速制作に取り掛かった。実験室で行われる化学反応といっては大げさだが、創作棟にある段ボールや木片を材料に、アイディアは一気に模型となって現れた。それらが作家の頭の中から次々と現れるとはいえ、アイディアというまだ目の前にないある種の想像に手が触れる時、木の扱いはやはり容易ではない。設計に使う数式はインターネットでも見つけることができるが、数式が正確であっても実際の木の扱いは異なり、わずかなズレがあっても形を組めなくなるため、木の模型は何度も繰り返し作ってみることが必要になる(2)。また、滞在制作など異なる土地に移動して制作するたび、そこで使われている木材の性質に合わせて制作方法を模索する。今回の作品で薄い木を合わせて少しずつ湾曲した形を作るためにも、木が割れないように適切な材を探し何度も試作が重ねられた。

滞在中、アイディアが決まると設計図も描かずに早速制作に取り掛かった。実験室で行われる化学反応といっては大げさだが、創作棟にある段ボールや木片を材料に、アイディアは一気に模型となって現れた。それらが作家の頭の中から次々と現れるとはいえ、アイディアというまだ目の前にないある種の想像に手が触れる時、木の扱いはやはり容易ではない。設計に使う数式はインターネットでも見つけることができるが、数式が正確であっても実際の木の扱いは異なり、わずかなズレがあっても形を組めなくなるため、木の模型は何度も繰り返し作ってみることが必要になる(2)。また、滞在制作など異なる土地に移動して制作するたび、そこで使われている木材の性質に合わせて制作方法を模索する。今回の作品で薄い木を合わせて少しずつ湾曲した形を作るためにも、木が割れないように適切な材を探し何度も試作が重ねられた。

木は物理的に硬くとも、本来生き物であり概念的な生命の柔らかさを持つ。その自然物に対して人工的な形を与えることで、真逆の関係を表すだけではなく、シティフォンの作品が木を素材とすることによる作用は大きい。

作家は過去に、装着可能で翼の動きの仕組みを兼ね揃えた彫刻を制作しているが(fig.2)、イカロスがロウと羽根で作った翼を想起させるこの木の翼では、実際に空を飛ぶことは不可能だ。メカニズムが持つ能力にも関わらず、彫刻として木で作られる装置はその機能を発揮しない。身体機能を改良するどころか、実際には人の動きを拘束し、制限してしまうことになる。

そうした目的への失敗は、人が人以上のものになろうとすることで起きる矛盾を暗示させている。シティフォンの作品にとってここでいう「失敗」とは、マイナス要素としてではなく、実際には機能しない、むしろ機能させないことでの矛盾の提示による見る者への問いかけである。機能の喪失は、逆にメカニズムにおけるデザイン性に見る者の目を引き寄せ、更に想像を喚起してその先のストーリーを作り上げさせる。それによって彫刻は想像上の装置として機能し始めることができるのだ。

一方、実際に彫刻が動く様子にある迫力と可笑しみは、矛盾から見える逆説的な人間像と、装置として不完全と成らざるを得ない虚しさをユーモラスに作品の中へ内包させることに成功している。そのメカニックな様相に隠れた人間味が、愛敬をもつ所以だろう。彫刻としての作りから見れば、理論に適った強さに対して、手仕事の繊細さや機能としての弱さは、その差が大きいほど互いの印象を強める。

一方、実際に彫刻が動く様子にある迫力と可笑しみは、矛盾から見える逆説的な人間像と、装置として不完全と成らざるを得ない虚しさをユーモラスに作品の中へ内包させることに成功している。そのメカニックな様相に隠れた人間味が、愛敬をもつ所以だろう。彫刻としての作りから見れば、理論に適った強さに対して、手仕事の繊細さや機能としての弱さは、その差が大きいほど互いの印象を強める。

シティフォンは、そういったアイロニカルな表現を通してテクノロジーの進化、さらには人間とは何かを問いかけてきた。与えられた能力を超えようとすることで逆に制限させてしまう。言い換えれば、人間は人間でしかなく、それ以上にはなれない。矛盾を孕みながらも、作り続ける、進化を求める。そこには、「最終形」を持たずに完成することのない作品を制作し続ける作家の姿勢が重なってくる。作家としてあり続けるための姿とはいえるが、先に述べた実験室の中で、並べられた作品を作家の技術の向上や積み重ねられる経験に合わせて改良し続け、さらに作っていく過程を公開することもあるその姿勢は、制作自体が物を作る喜びと同時に自身の生き方を表し、つまり自らの問いへの一つの答えとなっているのだろう。

「コクーン」の中で、人は変化、進化していく過程にある。過去作でみられるロボットのような手の形や、人が装着するための形態とは異なり、すっかり人間の身体を覆ってその形を失わせることにより全く別のものへの変化を予期させる。これらの装置は人の想像を必要とするが、矛盾や不可能を取り払うことができないにしても、想像力はまだ目に見えないものに対して前進する力であり、生きていく過程において大きな存在なのだと改めて気づかせる。また、それを現実に変え進化する力を持っているのも人間であろう。

「コクーン」の中で、人は変化、進化していく過程にある。過去作でみられるロボットのような手の形や、人が装着するための形態とは異なり、すっかり人間の身体を覆ってその形を失わせることにより全く別のものへの変化を予期させる。これらの装置は人の想像を必要とするが、矛盾や不可能を取り払うことができないにしても、想像力はまだ目に見えないものに対して前進する力であり、生きていく過程において大きな存在なのだと改めて気づかせる。また、それを現実に変え進化する力を持っているのも人間であろう。

作家の投げかける問いは、人に内省を促し変化させる形となって表れ、メッセージを包み込む。それと同時に、サナギであり卵のようにも見える形は、想像を生み出すには象徴的だ。そこから羽化し、生まれ変わって現れる次の装置が、見る者の新しい想像によって動き始めることを期待する。

- 展覧会関連イベントのレクチャーでの発言(2016年12月3日)。

- 同上。 »